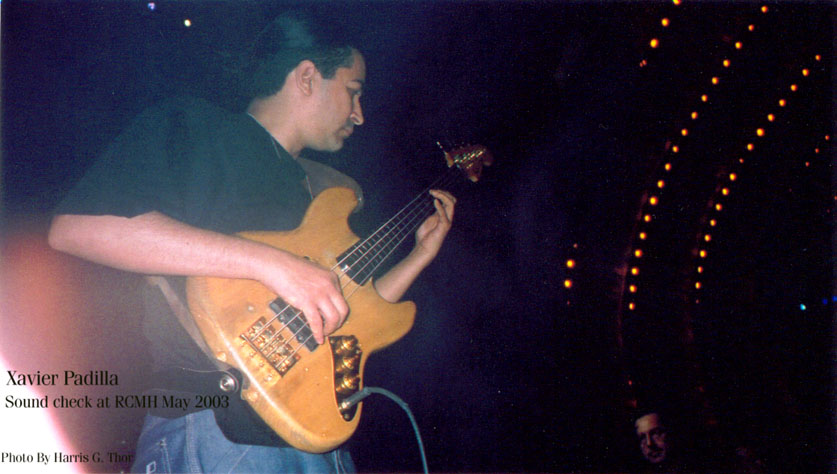

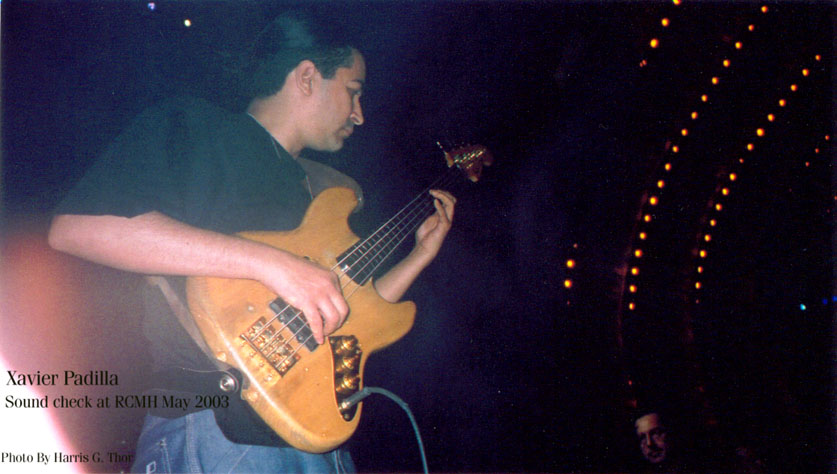

Xavier Padilla

Brought to you by the HG Thor Guitar Lab

Foreword:

After many emails and then actually meeting Xavier

Padilla, I have come to believe

that he is a true artistic genius, an original thinker tempered by a study of

history, has solid concepts yet is a good listener with an open mind combined

with a strong sense of global oneness. A unique and powerful combination of

characteristics which are bound to establish his presence vividly in the

contemporary music scene, and for years to come. His killer chops and unique

perspective on bass playing, technique and deep historical understanding of

music and its mechanics have reshaped my thinking on many fronts. Xavier has

many new revolutionary thoughts on bass design, music notation, and is an

oustanding composer/arranger. I am honored to be a part of his life, as his

friend and luthier. This page will be an ongoing forum for Xavier's ideas, so

please check back often for updates. -Harris G. Thor

Xavier on the HG Thor epoxy technique:

On bass technique:

Music notation as it relates to electric bass:

Bass playing positions:

Words from Xavier Padilla about the HG Thor Epoxy technique:

"I should say first that I've never played before a

fretless bass with an epoxied fingerboard. The effect epoxy produces in the

sound, for a first timer like me, is amazing: everything is brighter and all

details come out clearer. As an instrument, I feel like the bass becomes more

sensitive. Vibrato, which is essential in fretless playing, becomes more

responsive, as if the rotating movement of the finger upon the string was now

better "heard" by the neck.

"Epoxy may be the right transitory layer connecting the

metal hardness of a string and the relative softness of the hard wood's neck.

Without this epoxy interface a lot of physical data is surely gone. In that

sense, I guess the number of epoxy coats is crucial in determining a good

balance between both wood and metal sonic properties. I would say that with

epoxy coats on the fingerboard a fretless electric bass still gets a woody

sound, but with a new element that brings it closer to that of a grand piano. I

definitly get that with my Jaco bass now, which I didn't get before with the

original polyester finish it came with.

"I now realise that in 22 years or so of bass playing I've never comme

accross a neck so well prepared for playing as this. I've been playing it now

for about four hours since yesterday, and it's like I've never played a fretless

before and didn't know what a pleasure it can be. Only for this you have

dramatically influenced my life. I would really like that great fretless players

(like Pino Palladino), you know, really famous ones (not like me) become your

customers as well. If I meet one, I'll wash his head (remember I got one bass

player, perhaps the greatest on earth right now, playing for a bassdom holder

like Joe Zawinul). If Fender ever decides to produce another epoxy fretless, you

should be the guy.

Xavier on bass technique: Back to top

"I consider an instrument as an extension of the human

being. This piece of wood laying under the strings is something I carved and

installed myself on my main bass, a 77 jazz bass, around 1988. I have always

complained about the flat surface of almost every pickup there is, I've never

found reasonable that they are flat when the strings actually decribe a curve.

Why not have them to match that curvature? There are many obvious reasons

supporting my approach. The fullest sound on any stringed instrument is achieved

with a downward (towards the body) struck of the fingers. This was best

developed through the evolution of the classical guitar, and is called

"apoyando".

Sideward strucks result in a less fuller sound, as well as

the pull out strucks, which called "tirando". The "apoyando" struck seems to put

into action the instrument as a whole, in acoustics terms, and therefore get the

most out of it. Now, the guitar strings present narrower distances between them

than the electric bass ones, and therefore the articulating fingers, index and

middle, don't go as deep between them as they do on the electric's. Going too

deep for the fingers in "apoyando" plucking translates into a slow articulation

because it demands an extra physical movement of the fingers, which travel a

longer distance, and therefore ask for more energy to be spend. Here is where an

apropriate underneeth surface below the strings on an electric bass would play

an important compensatory role. Unfortunately, the flat surface of pickups do

not serve this purpose, almost forbbiding a righteous approach at this place of

the instrument where plucking "apoyando" is so important. Pickup designers might

argue that their job is principally electronic, not ergonomic. Perhaps they need

the imput from players asking for that sort of thing. Now the Fender shape, for

example, including that of the pickups, is called classic because so many great

players, some of which were actually geniuses, made career with them. But great

players and geniuses, in my opinion, would have made career on no matter what.

In fact, the whole area from the end of the fingerboard to the bridge saddles

should present an adecuate underneath surface for the fingers in order to allow

the player to profit from a legitimate, good articulating technique. We can

always reserve a very specific area for other techniques like slaping and

popping if necessary.

I can strike them apoyando due to two things:

1)  I do not hold a

Fender bass like it is conventionally hold. I use two straps (one in the normal

fashion and another that's attached to the lower pin and goes around my waist

and returns to the same pin) to get the bass in a more upright fashion, which

changes radically the way my right hand approaches the strings. (The reason for

that posture of playing has to do with other things too, like diminishing wrist

angles for both hands, to gain better acces to the higher register, to fix the

position of the instrument relative the my body -independantly of my movement in

space- and diminish the weight on my left shoulder).

I do not hold a

Fender bass like it is conventionally hold. I use two straps (one in the normal

fashion and another that's attached to the lower pin and goes around my waist

and returns to the same pin) to get the bass in a more upright fashion, which

changes radically the way my right hand approaches the strings. (The reason for

that posture of playing has to do with other things too, like diminishing wrist

angles for both hands, to gain better acces to the higher register, to fix the

position of the instrument relative the my body -independantly of my movement in

space- and diminish the weight on my left shoulder).

2) I have built on my main bass (Fender jazz 77) a small structure that can be seen as a complex thumb/ring rest which provides a better hand positioning for that purpose.

But there are

also two inter-related limitations to apoyando:

1) High speed of alternancy

between upper and lower strings and

2)

radiused string disposition. The shorter the radius implicated, the less

probable the apoyando is going to happen

"Another underdeveloped issue on the electric bass

design, in my opinion, is thumb rest. But that's another whole story which

implicates a lot of different parameters of use, like the solution of medically

adviced dangerous wrist angles for both hands which remains untreated at present

in the modern standard electric bass design. There is a guy who I believe has

solved this problem of wrist angle

(http://www.littleguitarworks.com/index.html), but there is still a long way to

go before reaching the full electric bass "real" standard design. In Fenders

there are all the basic elements of the instrument, but they've been called

classic too early and mostly as a profitable marketing adventure. When I say

"real" I'm imagining something comparable to the violin or the cello, where

millimeters are so jealously preserved worldwide. Those millimeters are

almost like the official support for both instrumentalistic proven techniques and luthierie secular

achievements.

HGT: "What exactly would you like to see for a thumb

rest and playing geometry?"

"I have

designed a very special and unique system of right hand articulation. You should

see a picture. I use a different thumb rest for each string I play, in

combination with a ring finger hole/rest that put my ring finger to function as

a pivot for back and forth hand movement. Much of the system is intended to dump

the strings that are not being played. The thumb has the function of damping the

A and E strings when I'm playing the G and D strings respectively (when I'm

playing the G string and my thumb is on the A string,

the pinky is dumping the E string. The G string can only be damped by

the left hand, while the D is only damped with the first or second

finger after they play the G string. If I'm playing on the E string, my left

hand damps the other three strings and my thumb is resting in a thumbrest carved into

the bass body. Similarly, if I'm playing on

the A string the left hand is damping the G and D strings and the thumb

is resting in another thumbrest carved into the bass body). I'll try to

make a picture of this structure/base, it is really odd and was made to

my hand measures ...by myself.

I use a different thumb rest for each string I play, in

combination with a ring finger hole/rest that put my ring finger to function as

a pivot for back and forth hand movement. Much of the system is intended to dump

the strings that are not being played. The thumb has the function of damping the

A and E strings when I'm playing the G and D strings respectively (when I'm

playing the G string and my thumb is on the A string,

the pinky is dumping the E string. The G string can only be damped by

the left hand, while the D is only damped with the first or second

finger after they play the G string. If I'm playing on the E string, my left

hand damps the other three strings and my thumb is resting in a thumbrest carved into

the bass body. Similarly, if I'm playing on

the A string the left hand is damping the G and D strings and the thumb

is resting in another thumbrest carved into the bass body). I'll try to

make a picture of this structure/base, it is really odd and was made to

my hand measures ...by myself.

"I have also made thumbrests

on the back of the neck! It did weaken the neck seriously, but I

gained other things (I've always thought of my bass like a prototype for a future bass,

but allways stick with it !!). They had to be eight in number but due to

the neck/body joint I could only make six.

They are related to an eight position note-reading-fingering-system I figured specifically for the electric bass. This

is a very (very) extended matter I worked on for years and hope

be able to publish one day. It is an alternative system for reading fingerwise,

automatically, notes from the staff.

On music notation as it relates to the modern electric bass: Back to top

(To HGT) "I told once I will send you a text I wrote relative to a book I'm

preparing, now for years. Here you have it. Its a post I did in a forum and

includes parts of what is intended to be the foreword of my book, which is

called Note-Reading Fingering System For Electric Bass. As you will notice, once

you read the text, I'm sort of engaged in a history/evolution of the instrument

thing, which covers instrumental technique as well as instrument conception

(dessign). These two thing can only evolve together.

"I have even tought

of a bass made specially for reading music, based on the system I invented. In

the text below I don't say I have already invented one system, only that it is

necessary. I wanted to see the reaction among players in the forum I posted it.

I tell you, I was a very polemic forum:

"Open

letter to all of you who think -or do not- that electric bass players need a

legitimate fingering system for reading:

'To read music in general we must understand

first the standard music notation system, of course. But to read music with an

instrument it is required to know, in addition, the particular fingering system

of that instrument. That means that reading with an instrument is a more complex

task, for it supposes the good combination of these two independent systems.

While one is related to the eyes and the other to the hands, in the end both are

nothing but conventions that need to be learned separatedly first, as each

contains lots of specific information on its very own.

'It is a general

belief, though, that written music teaches the player along how to finger any

instrument, taking for granted that sight-reading notes from the staff would

lead our hands automatically to the right places. Unfortunately, this can only

be effective for instruments whose "closed physical structures" produce what is

called "fixed fingering systems", as in the case of saxophones and trumpets.

These instruments simplify enormously the inmediate fingering of first-time seen

material -and therefore the conversion of new music into live phenomena- because

all the notes they read find strictly non-flexible correspondencies on their

bodies, every pitch

disposing of just an exclusive physical place on

them.

'The electric bass, on the contrary, being an instrument widely

characterized for allowing many fingerings -and places of the fingerboard-

to

a single note, prompts instead the player to continuously choose where and

how the information is going to be handled. Its "open physical structure", in

itself a precious inherent flexible condition that favours the freedom to

personalize our playing, turns suddenly into an obstacle: the paradoxal

condition of been limitated by having so much to choose from.

'In

a sight-reading situation, knowing where all the notes are on the neck

not necessarily means to know how (that is, an exclusive or prioritary way)

to finger them immediately. The electric bass fingerboard presents, in fact,

too many wheres, and therefore too many hows.

(Not only that it has

many wheres for almost each note, but that each where doesn't contain exclusive

hows. Prioritary hows, in turn, are only possible if two or more wheres are

related as previously prioritary wheres!)

'If we didn╣t have always that

many options at hand while in a sight-reading situation, the mission of finding

instantly related fingerings on the bass wouldn╣t, as it does, consist on an

obvious display of choosy mental efforts. We would instead focus better on

interpretation and follow more confinedly the part. The complexity of the task,

however, doesn't seem to get us to the subconcious required reflexs.

'A

comparative regard upon the greatest variety of musicians shows that

sight-reading with an instrument is a task generally best covered by

instrumentalists other than electric bass players. Whereas for most instruments

"where" and "how" mean more or less the same thing, on the electric bass these

words can be so particularly dissociated that some diligent (but too courteous

maybe) professional rules, like giving the bass players the parts before anyone

else, are sometimes fully justified. Definitely we need an alternative method (a

system) to show us how to finger on the electric bass any written part

instantly!

'Too often we tend to think that the solution lies outside our

instrument. Incidentally, the general qualified advice of teachers and

professionals is to strive for improving our ability on what actually are only

"page matters", i.e. the half of the story: "train hard yourself on sight

recognition for pitchs, intervals and rhythms; get a degree of eficiency at

absorbing musical contents through the standard notation system". It is presumed

implicitly that by doing so the relative │instrument matters▓ would fall along

into place.

'From those qualified, official recomendations, the aspiring

bassist infers that reading much ahead on the staff is what it's all about, a

"gain-time" solution that really works against the abundant fingering choices

always available. But that's a deviation, a misleading omission which

unfortunatly most educators and players have been insisting on for decades,

disregarding the essential open structure of the electric bass as a real problem

in sight-reading.

'The topic of fingerboard employment has been usually

smoothed out behind the obscure nomination "reading skills", aluding to those

mysterious capabilities that all experienced players are suposed to have but not

one finally breaks down into a system for others (sometimes under the excuse

that "what works for me not necessarily works for you"). A doubtful, anyway,

propietary circumstance which evokes top clearences to sacred places, self

spreading mystifications, though in reality it might be nothing but the

idealization of an unsuccesfully conquered professional area. Meanwhile, it is a

well paying secret which usually we believe will be revealed to us if going to

the right schools and pros.

The problem lies decidely not in the page.

Our bass neck have a totally variable structure which does not tell alone the

player an exclusive way to approach them, the amount of theoretical

fingering choices being overwhelming: 80 locations on a Fender╣s neck where to

put a finger!

'At the same time, there are mostly 5 different possible

fingerings (if we use a standard position of one finger per-fret and

occasionally extend one onto a fifth fret) for each of these 80 finger-places.

That makes about 400 fingerings in all (5 x 80), to which it must be added the

fact that multiple locations do exist on the fingerboard for almost every single

pitch to be found on the staff. This, again, is an enormous exponential

increment of fingerings to choose from, which can only further complicate

reading. It tell us that out of all 36 pitchs actually contained on a typical

Fender, 6 are located simultaneously in 4 different places of the fingerboard,

10 found in 3 different places, other 10 in 2 places and only a small remainder

of 10 pitches located each in one exclusive place of the neck.

'On the

│fixed▓ structure of other instruments either do not exist multiple pitch

locations, or these are contained in much smaller quantities. A saxophone or a

trumpet, for example, only very exeptionally allows more than one fingering for

playing a pitch: generally just 3 notes can be played differently within the

saxophone╣s full extention, and there are only about 6 of the same sort in the

trumpet╣s (against 74 alternative fingerings -out of 26 multi-location pitchs-

on our bass!).

'On the other side, while those wind instruments allow the

player to │assume▓ the music that╣s being played from a steady physical base,

the electric bass player is obliged to move constantly in search of a place

(position) on the neck where to finger the notes. The best way to move

accordingly, says the common belief, is by looking for keys in the music as to

quickly define positions and fingerings. This also supposes to reduce the amount

of alternative fingerings to choose from along the course of a piece.

Nevertheless, this key dependency presumes that players would always be

conscious about the current key, which in reality is not so. Instrumentalists

aren╣t always informed of the key by the page, nor the notation system is

intended to count on their ears. Even sometimes there are not tonalities at all

in a tune (atonal music) to provide key positions or sugest any of our

eventually well learned modes.

'Let us be clear, electric bass players

have tried for years to get away with what they╣ve got, developing fast and

complicated shops that rely exclusively on their capabilities for looking much

ahead into the page (a skill they╣ll try to develop not just in order to avoid

been surprised by tricky lines, but to quickly figure out fingerings for

upcomming written passages -which already shows a double responsability).

Subsequently, they would be constantly turning back their eyes rapidly into the

fingerboard as to perform imperative shifts without failure, but then getting to

finally watch the conductor (if there is any) only in their dreams!

'The

eye-to-page effectiveness is in obvious contradiction with the eye-to-neck

dependency.

'Please, then, let us get to work and find once and for all a

solution to this dilema (one that would work for all of us). The books we own

don't have it. The one we are looking for hasn't been written yet. So let us

find a fixed fingering system (which I believe to be the apropriate kind) that

would work solidly in every case, and avoid passing this problem on to the next

generation of players over and over.

Xavier Padilla"

On bass playing positions: Back to top

The problem of standing vs sitting

playing position examplifies how little luthiers have thought about designing an

electric bass that stays exactly the same in both ways. But it isn't exclusively

their fault, since we as players are also responsible for telling them what we

need, which in this case is crucial. Honestly, when we

regard the situation, what an omission!

This shows

that practice, practice and practice, as Mr Anyone says, and which is of course

a positive thing to do, won't be enough for him: he"ll need practice, practice

and practce in sitting position, and then he'll need practice, practice and

practce in standing position.

Your training of muscles in one position doesn't address

the other if the bass you are using doesn't stay "the same"

in both ways.

If things, at present, were more developed

(as we tend to think they are) such an elementary detail would have been

already covered and standarized by the majority of bass factory conceptors.

If times were so, normally before buying an electric bass we should have to ask

the vendor what are we buying: a "one-way-playing" instrument or a

"both-ways-playing" one. But today we wouldn't be understood inmidiately if

asking so: the state of things regarding these (and other) design topics isn't

really so evolved yet, as the prices we pay would make us believe.

To avoid treating superficially

(or pseudo-solve) the problem of sitting vs standing, we should try to talk more

about instrument design, instead of advicing others to hold the bass higher, or

put efforts in looking for similar shortcuts. As someone pointed out in an

internet forum, "holding the bass higher makes the right hand wrist bent at an

extreme angle". Angled wrists are highly dangerous on both hands and are

therefore medically counter-recommended, which is another issue to be properly

addressed in bass design.

Nowadays, if we find an electric bass that can be hold and

played in exactly the same position while sitting or standing, it would be an

exceptional instrument (when, in fact, it

should almost be the rule).

It

is clear that, as of now, all efforts and research on bass conception have been

concentrated on materials, electronics, hardwear, esthetics and construction

methods. Ergonomics, or which is the same, human oriented instrument design in

conjuction with human oriented playing techniques, represent but a very small

percentage. We rely on designs over-exploited and sacralized by mass production

companies that say too little of how ergonomical or instrument could be today.

Xavier Padilla

All rights reserved. Copyright 2003 and Published 2002,

2003 Xavier Padilla, Fernando Xavier Padilla Delgado, Harris G. Thor,

HG Thor Guitar Lab